a sort of review by Daniel Darwin

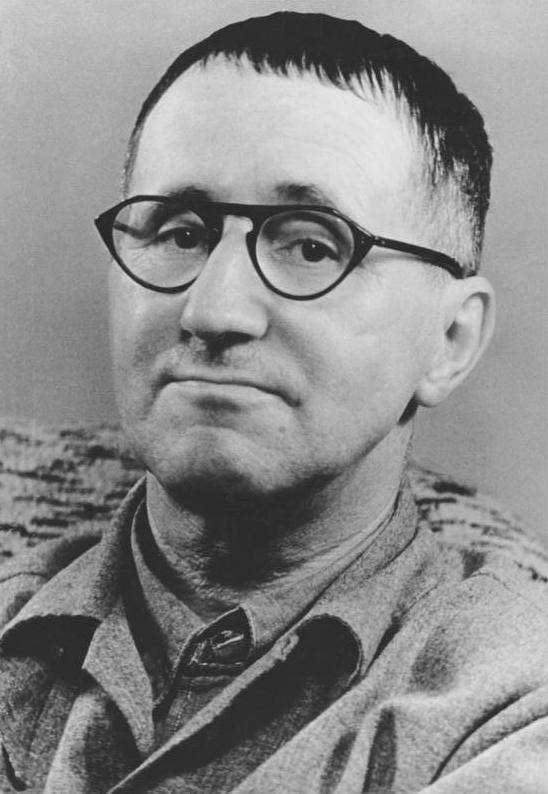

I just watched the third to last performance of Bertolt Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle [trans. Eric Bentley] at Theater For A New City, put on by a bright young company named Pipeline, and directed by Anya Saffir.

I don’t write reviews. Largely because I find I always end up talking about the dramaturgy of the play and not the quality of the production. And also because I find I seldom have anything to say. A bad production makes me foam at the mouth, and a good one leaves me speechless; neither of these conditions are very conducive to commentary.

But I’m compelled to write about The Caucasian Chalk Circle – because it was excellent, because it’s one of my favorite plays, and because it was a revelatory experience for me.

One seldom gets the chance to use the word “inimitable” in a context that doesn’t bleach the word’s charge. So when I write that Ms. Saffir’s direction was truly inimitable, I write it with a deep [and hoity toity] satisfaction. This was the first time I’ve ever seen Brecht staged. With a body of work as fat as his, you’d think that the downtown scene would be brimming with productions of his plays and operas. But the thing about Brecht is that if you’re going to do him, you better make damn sure you do him well. Not necessarily to do him “justice,” but because if you don’t direct his plays with extreme care and precision, they don’t work. A mishandled Brecht script is about as riveting as a loaf of bread.

I think the scarcity of attempts to produce his plays comes directly from the fact that directing a play like The Caucasian Chalk Circle is an exercise in bricolage. It implies a precise stitching together of vastly different aesthetics – vaudeville, variety show, stark realism – and vastly different vernaculars – sung and spoken verse, high prose, colloquial – all towards the creation of a well-oiled and violent machine. One that pulls the spectator through an array of layered worlds, half-stories, and shifting characters in such a way that meticulously plucks and prods at our empathy. It lets us feel just enough to feel the feeling’s abrupt absence; it lets us laugh and then catch ourselves laughing; it lets us almost cry and then wonder why. A Brecht play done right is Frankensteinian – cruel and wondrous, gentle and menacing. And to direct it well, you need a scalpel in one hand and soldering iron in the other. Anya Saffir wields both, and her creation is a thing of beauty.

Before I delve into what struck me about Anya’s direction, I feel I should mention that the production was, on the whole, magnificent. I’ve seen a fair amount of Pipeline’s work in the past, but never before has the ensemble moved in such a fluid, thrilling way as they did today. This was in part because today’s play is the deepest and most challenging work they’ve taken on; they seem to have had time to test their mettle as a troupe and now have honed the instincts and trust necessary when really getting your hands dirty on a piece like this. The set design, costumes, and lighting all worked together in laying the world of this parable within a play. The designers balanced a vaudevillian air with a post-war grisliness, and tethered us to a complex story that – without their hintings – might easily have left us behind. The music was splendid and raucous, effortlessly integrated into the text and the performances. I’m also just a fool for actors with instruments [when the Grand Duke straddled the cajon I just about peed my pants].